What are we doing about climate change?

August 28th, 2015

by David Maleki

We know that cities are key to tackling climate change, so how can we support them in mastering this challenge?

Here are the 3 steps that we, in the Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative, take to help our partner cities find ways to reduce their carbon footprints and climate change vulnerability. At every stage, we work closely together with our colleagues in the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) sector divisions, especially the climate change and disaster risk management teams.

Informal settlements prone to landslide risk in Xalapa, Mexico, Photo by David Maleki

1. What’s the issue?

If we want to better understand how our partner cities can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vulnerability, we first need a clear picture of the challenges they face. Climate change can’t be dealt with in isolation, it is a crosscutting issue that affects and is affected by a wide range of activities. This is whywe assess many different topics at the beginning of our work in a city, using a set of at least 117 indicators. Many of these indicators are closely connected to the challenges of climate change.

For example, analyzing data collected from Xalapa, Mexico, we learned that more than 40% of its citizens live below the national poverty line. What does this have to do with climate change? The statistic indicates that a considerable part of the city’s population most likely has a very limited ability to cope with the negative impacts of climate change.

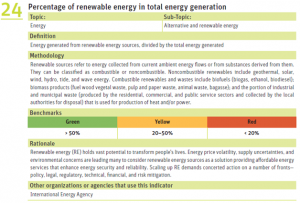

Our indicator sheets provide detailed guidance on how to measure and evaluate a city’s performance on a variety of topics.

In another Mexican partner city, Campeche, we found a rather low share of renewable energy sources and green urban space. There might thus be a high potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion and for creating recreational parks that also serve as carbon sinks.

In addition to collecting sectoral data, we also consider climate change-specific indicators. For example, have climate change considerations been incorporated into the city’s planning instruments? Are greenhouse gas emissions assessed and monitored? These indicators help assess the strategic, legal, and regulatory framework needed for taking effective action. Together with the sectoral indicators, they provide a comprehensive initial assessment for our partner cities.

Nevertheless, to make informed decisions in a changing climate, more in-depth analysis is required. For this reason, we commission a set of three interrelated studies for each city that focuses on the nexus of climate change and urbanization. Firstly, we take stock of the city’s current emissions through a greenhouse gas inventory, calculate different emission scenarios, and propose measures to reduce the local carbon footprint. Secondly, we determine the vulnerability of the city to a range of natural and man-made disasters, from inland flooding to landslides and droughts, and assess how climate change might affect them. Thirdly, we develop urban growth scenarios that help avoid carbon-intensive urban sprawl and flag areas where urban growth should be restricted due to disaster risk.

In Jamaica’s tourism capital Montego Bay, we found that the current growth pattern will expose approximately an additional 5000 citizens to extreme flood events by 2030, almost ninety times more than in a smart-growth scenario.

Maps like this smart-growth scenario for Montego Bay help city planners to avoid carbon-intensive development and areas prone to disaster risk.

2. Where do we start?

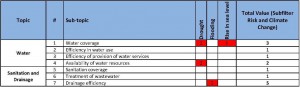

Once the indicators and the studies have provided a clear picture of a city’s needs, our partners have to decide where to begin. This is where our Climate Change and Disaster Risk Filter comes into play. What started as a qualitative evaluation based on focus groups and expert interviews now offers a more systematic and objective approach to identify the role that each sector of the city can assume in reducing emissions and vulnerability. Together with a public opinion survey and an economic cost analysis, the filter determines in which sectors taking action is most important to spur sustainable local development.

This table is an excerpt from the Risk and Adaptation dimension of our Climate Change and Disaster Risk Filter for Asuncion. The importance of the links between subtopics and hazards receives a score based on the results of the studies. Similarly, the links between subtopics and greenhouse gas emissions are evaluated.

When deciding on which areas to include in the ESCI Action Plan for Paraguay’s capital Asunción, the filter’s multi-criteria analysis put solid waste management on the agenda. While there seemed to be no significant economic incentive to improve waste collection and treatment, and citizens were rather worried about more imminent concerns like public safety, the filter found that due to significant opportunities for reducing Asunción’s greenhouse gas emissions, the sector should not be ignored. Simply capturing the biogas in the Cateura and El Farol landfills, for instance, could reduce Asuncion’s annual emissions by more than 7% by 2050, compared to a business-as-usual scenario. The Climate Change and Disaster Risk Filter helps us adopt a broader and more long-term perspective when evaluating the need to take action.

3. Get to work!

Once we know what to do and where to start, the next step is to take action. Based on the indicator assessment and the consequent prioritization, we develop Action Plans with our partner cities. These plans lay out strategies and concrete projects to overcome a city’s major development challenges. Wherever relevant, climate change considerations are either mainstreamed in sectoral activities or addressed through specific project proposals.

The ESCI Action Plan for Mar del Plata in Argentina, for example, identifies investment needs of more than $300 million that are directly relevant in the context of climate change. The projects proposed include the installation of a 10 megawatt wind park that would reduce the city’s carbon footprint, and improvements of the drainage infrastructure that could help manage the increase in floods expected to be caused by increased rainfall and rising sea levels.

In order to ensure that the plans result in concrete actions, we support our partner cities in mobilizing the required funding. This can be very challenging, but by leveraging local resources and through partnerships with national governments, other donor organizations, and the private sector, we work to come up with viable financial solutions.

In Barranquilla, Colombia, the IDB will provide a loan of approximately $70 million through Colombia’s national development bank Findeter for a range of projects that are expected to include a control center improving the city’s ability to respond to natural disasters.

In La Paz, Mexico, we facilitated the establishment of a public-private partnership to build a 1.34 megawatt solar power plant that is expected to decrease the local government’s CO2 emissions by 40,000 tons over the life time of the project.

What challenges do we face?

We repeatedly face two major challenges while working with our partner cities on climate change.

The first is data availability. The global climate system is complex and working on climate change therefore always involves uncertainty. However, while projections exist for the global, regional, and, in some cases, even national level, data on the local impacts of climate change is harder to come by. In addition, many cities lack the statistics and databases necessary to estimate their emissions and quantify even their current disaster risk. Complete records of electricity consumption are essential for estimating greenhouse gas emissions in the energy sector, statistics on vehicle and fuel types for determining emissions from transportation. For identifying areas prone to flooding, details on past inundations as well as topographic data of adequate resolution are required. In some cases, we can close gaps within the scope of our studies, in others, we have to use estimates, proxies, or substitutes to make the assessments that we need.

Also local capacity can be a challenge. Many intermediate cities in Latin America and the Caribbean have not yet integrated climate change considerations into their structures, budgets, and policy-making. To support local officials in making optimal use of the analytical tools that we provide, we try narrowing this gap by offering targeted workshops and, starting this year, continuous on-the-job training for using the tools that we provide.

Working with many different cities across the region provides us a unique opportunity to learn what works and what doesn’t. Our goal is not only to help our partner cities to take action on climate change, but also to develop and disseminate best practices for addressing urban climate change challenges that can be replicated beyond the Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative. This means, of course, that we are always curious to learn more about how others deal with these issues.

If you would like to contribute to this discussion, feel free to share your experiences with us in the comment section below.

Tags: Action Plan, asuncion, barranquilla, campeche, climate change, esci, indicators, mar del plata, methodology, Montego Bay, Xalapa

The Gleaner reserves the right not to publish comments that may be deemed libelous, derogatory or indecent.

To respond to The Gleaner please use the feedback form.

One Response to “What are we doing about climate change?”

- Three ways the Caribbean can strengthen financing for private companies

- Learning about Jamaica’s Forests by Hiking the Blue Mountains

- Making People Happy

- US Supreme Court: One Less Known Example of How a Supreme Court Decision, Shapes Up Judiciary Reality in the Caribbean

- Crime in Paradise: Preview of Forthcoming IDB Study on Crime in the Caribbean

- Caribbean Diaspora: How Can They Finance Development in the Region?

- Zika Virus and the Economic and Human Reproductive Health Implications for the Caribbean

- Proper Solid Waste Management Involves all of us

- Victimization surveys: 3 common mistakes to avoid

- Social Innovation: The way forward for Civil Society Organizations

David global warming is the greatest scam since Piltdown man. The science behind it is faulty and has failed every test of science. It shows the new emergence of a fallacious merging of religion with unproven scientific theories. How? Proponents rant about belief and prophetic predictions instead of double blind studies. Find me one double blind study that concluded that carbon dioxide drives temperature variations and then if you do explain how come for the past twenty years how temperatures have flatlined while carbondioxider has continued to increase in the atmosphere.